Siri 29 – Memperingati Perjuangan Pembebasan Aktivis PSM EO6 (2011) – Ulangtahun ke–10

#HariIniDalamSejarah

28 Julai 2011

Mogok Lapar Untuk Keadilan

Pada hari ini, Dr Kumar membuat keputusan untuk melancarkan mogok lapar membantah penahanan tanpa sebab yang berterusan terhadap beliau dan lima lagi kepimpinan PSM. Berikut adalah kenyataan komrad Rani yang telah berjumpa dengan Dr Jeyakumar;

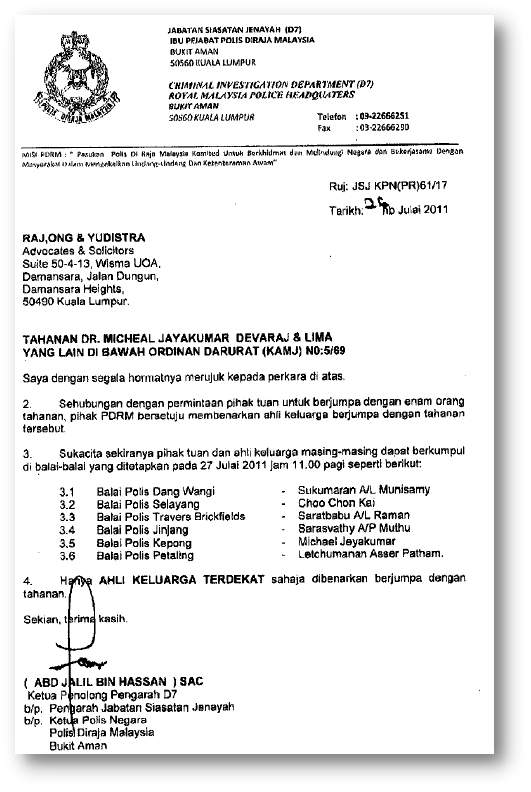

“Apabila saya jumpa suami saya Dr Jeyakumar pada 11 pagi semalam, 27 Julai 2011, beliau suarakan perasaannya yang sangat hampa dan kecewa dengan pendirian polis dan kerajaan terhadap enam aktivis PSM yang ditahan di bawah EO sejak 2 Julai 2011.

Menurutnya, polis enggan berganjak dari posisi asal mereka walaupun PSM 6 telah bekerjasama penuh dan menjawab kesemua soalan yang ditanya semasa soalsiasat dijalankan. Walaupun polis tidak dapat sebarang bukti untuk menjustifikasikan pertahanan lanjutan, namun beliau pasti tempoh tahanan mereka akan dilanjutkan sebab polis dan kerajaan ada agenda sendiri dan mempunyai tujuan untuk memangsakan PSM6 .

Maka Dr Jeyakumar telah memberitahu saya bahawa beliau akan mulakan mogok lapar pada 28/7/11 untuk mendapatkan keadilan. Beliau akan teruskan mogok lapar sehingga kesemua PSM6 dibebaskan atau dituduh dimahkamah. Saya cuba menasihatkan beliau untuk tidak berbuat demikian kerana risau akan kesihatan beliau tetapi beliau bertekad mahu meneruskan mogok lapar kerana berpendapat

- Walaupun tuduhan keatas mereka adalah hanya pengerak BERSIH dan ini dinafikan oleh 6 orang tetapi polis sengaja mahu kaitkan mereka dengan tuduhan ini

- Walaupun sudah berkali-kali dikatakan PSM tidak ada kaitan dengan PKM dan PSM tiada niat untuk kembangkan fahaman komunis dan selama ini semua aktiviti PSM adalah terbuka dan transparen, tetapi polis cuba memaksa, mereka (frame up) tuduhan-tuduhan palsu keatas PSM 6

- Tuduhan menghidupkan komunisme ini hanya berdasarkan beberapa t-shirt dan kebelakangan ini polis sedang bergiat “frame-up” tuduhan baru dan menurutnya ini berdasarkan lawatan-lawatan pemimpim PSM ke luar negara atas jemputan parti sosialis lain di dunia dan cuba bertokoh tambah bahawa PSM ada hubungan rahsia dengan PKM di Thailand.

Dr. Jeyakumar menafikan semua tuduhan palsu ini, semua soalan polis menjurus untuk mengeluarkan satu cerita karut untuk melanjutkan tempoh tahanan.

Dr Jeyakumar memberitahu polis dan kerajaan supaya bersikap jujur dan review kerja-kerja dan aktiviti PSM dalam 13 tahun sejak ia ditubuhkan. Di mana semua aktiviti PSM adalah terbuka dan dan jika PSM mengkritik kerajaan BN, itu adalah hak demokratiknya.

Menurut Dr Jeyakumar, beliau telah memberi kerjasama penuh sejak direman di mana beliau telah menandatangani 3 laporan termasuk laporan 45 muka surat di Pulau Pinang. Sekarang SB telah sediakan report dengan 80 mukasurat tetapi Dr Jeyakumar buat keputusan beliau tidak akan tandatanganinya kerana beliau melihat kesemua siasatan sebagai sia-sia sahaja. Polis masih ‘menembak secara liar’ (shooting wildly).

Oleh itu, Dr Jeyakumar telah hilang kepercayaan kepada polis untuk melaksanakan isu ini secara adil. Beliau menuntut supaya Menteri Dalam Negeri mainkan peranan untuk membebaskan atau hadap mereka ke mahkamah. Sehingga hari itu beliau akan buat mogok lapar”

Ketua parti MIC, Dato G Palanivel juga meluahkan rasa ketidakpuashatian terhadap kepimpinan Najib yang terus menahan kepimpinan PSM. Beliau menyeru agar mereka dibebaskan segera.

Ketua parti MIC, Dato G Palanivel juga meluahkan rasa ketidakpuashatian terhadap kepimpinan Najib yang terus menahan kepimpinan PSM. Beliau menyeru agar mereka dibebaskan segera.

Ahli Parlimen Dr. Mujahid Rawa, Ahli Parliament Parit Buntar mengecam penahanan PSM EO6, berikut adalah kenyataan beliau,

Ahli Parlimen Dr. Mujahid Rawa, Ahli Parliament Parit Buntar mengecam penahanan PSM EO6, berikut adalah kenyataan beliau,

“Saya begitu simpati dengan dengan penahanan enam anggota PSM yang ditahan di bawah Ordinan Darurat atau Emergency Ordinance (EO) di atas kesalahan “menentang Yang di-Pertuan Agung” kononnya menghidupkan fahaman Komunis! Saya yakin saya tidak keseorangan menyatakan simpati terhadap mereka dan keluarga mereka yang ditahan, seluroh rakyat yang cintakan keadilan pasti “meluat” dengan lagak regim yang sedang nazak sekarang terkial-kial cuba mempertahankan keabsahannya dengan cara yang menjijikkan.

Apatah lagi dalam suasana simpati ini, saya mengenali YB Jeyakumar, seorang komrade yang gigih memperjuangkan hak rakyat marhaein. YB Sungei Siput ini terkenal sebagai seorang sosialis dalam makna yang positif dan memperjuangkan suaranya melalui saluran resmi PSM dan dirinya sebagai Ahli Parlimen. Penangkapan mereka di ambang 9 July di Pulau Pinang adalah satu yang malang bagi hak kebebasan rakyat untuk berkumpul dan menyatakan pendirian mereka. Penangkapan mereka memutarkan jam ke belakang untuk rakyat Malaysia yang sudah 59 tahun merdeka.”

Pada ketika itu, PSM bersama dengan Suaram juga telah membuat keputusan untuk melancarkan suatu protes candle light vigil, bermalam .’overnight’ pada 31hb Julai sempena lengkap 30 hari PSM EO6 ditahan. Dirancang bahawa protes semalam itu akan berakhir di Bukit Aman pada pagi 31 Julai, 2011.

Dari desakan berterusan, Ketua Polis Negara Tan Sri Ismail Omar mengeluarkan kenyataan bahawa tahanan EO6 sebenarnya ‘dilayan dengan baik’. Beliau enggan memberikan apajua jaminan yang mereka akan dibebaskan dengan alasan penyiasatan beterusan.

Dari desakan berterusan, Ketua Polis Negara Tan Sri Ismail Omar mengeluarkan kenyataan bahawa tahanan EO6 sebenarnya ‘dilayan dengan baik’. Beliau enggan memberikan apajua jaminan yang mereka akan dibebaskan dengan alasan penyiasatan beterusan.

SUHAKAM juga mengecam tindakan polis yang mengunakan alat pengesan pembohongan yang digunakan terhadap tahanan Letchumanan dan Sarasvathy. SUHAKAM menuntut suatu pertemuan dengan Ketua Polis Negara susulan berita bahawa tahanan telah dipaksa untuk mengambil ujian tersebut.

Suatu protest candlelight vigil juga diadakan di Pulau Pinang, sekitar Kompleks Penyayang.

Siri #HariIniDalamSejarah ini akan menjejaki usaha PSM dalam Perjuangan Membebaskan Tahanan PSM EO6 sehingga hari mereka dibebaskan pada 29 Julai, 2011. Nantikan kiriman kami yang seterusnya.

#PartiSosialis

Untuk maklumat terkini, sertai saluran Telegram PSM di

Untuk maklumat terkini, sertai saluran Telegram PSM di  t.me/partisosialis

t.me/partisosialis

Untuk maklumat terkini, sertai saluran Telegram PSM di

Untuk maklumat terkini, sertai saluran Telegram PSM di